Whitepaper

Social Housing: Radical Reform Through Better Collaboration, Interdependent Working and Technological Innovation.

Kate Davies Ex CEO of NHG has

Published This Social Housing Whitepaper.

Introduction

This White Paper has been written to capture issues troubling the people who run housing associations, and those they serve, and suggests how information technology could aid a breakthrough. For over 30 years, I worked in social housing for local authorities and housing associations. Across my time in the sector, although technology has increased our productivity and provided solutions to some of the age-old problems, the digital age potentially offers exciting, new possibilities. Over six months I have sought views, read papers and researched options. I interviewed and took submissions from over 20 different leaders both in housing associations and those providing services to them. Everybody who took part in the research was motivated by a desire to improve the service offered to the residents of social housing and felt that digital and technology had a key role to play. However, I am solely responsible for the content and proposals.

I hope to show the importance of interdependent working enabled by information technology, harnessing the growing significance of data; and demonstrate its value in empowering tenants.

Social Housing A proposal for Radical Reform

Let’s start working

together.

Collaborative working between housing associations.

Residents welcomed to influence association plans.

Launching the national database of social homes.

Housing association homes routinely upgraded.

Data driven decision making and resources efficiently deployed.

Housing associations today – what is the problem?

TENANT DISSATISFACTION

It is rare to watch the TV or read the news without housing associations coming in for significant criticism. The negative views boil down to the disappointing quality of our homes. The English Housing Survey 2021-22 reveals that 25% of social tenants are dissatisfied with their accommodation (compared to about 5% of homeowners). Of course, associations apologise and try to rectify the problem. Nevertheless, as time goes by nothing fundamental seems to change. Maybe the problems are more deep-seated than we once imagined.

POLITICAL CHOICES AND FINANCES

Why have we allowed social housing stock to get so run down and dated? In truth, the backlog of repairs is caused by the political decision not to fund major upgrades or refurbishments over many years. Rents are restricted by government and specific grants for stock renewal, adaptation, safety and sustainability have dried up.

The reality is that the significant funding needed to update housing association homes has been cut. Unlike local authorities which benefited from multimillion pound “Decent Homes” investment programmes, associations were expected to invest from their surpluses. However, while local authority building programmes were curtailed, the sector was also asked to supply thousands of new social homes So, housing associations have indeed diverted surpluses into new build to house more homeless families. This was a political priority at the time, and an unspoken assumption was that those already housed were considerably better off than homeless people. Consequently, essential re-investment programmes were limited to a “good enough” level – a level we now regard as sub-standard.

Although building new homes is urgent and essential, this must never be at the expense of social tenants or their homes. Value needs to be put back into existing properties. The underlying, historic failure to invest has created a problem which will not go away and will only worsen. However, the inadequacy of past and current investment programmes presents itself as a failure of housing associations to do their job properly, with politicians, regulators and tenants regularly claiming the sector is run by idiots. In fact, associations are caught in a desperate downward spiral of burning up rent money on short term fixes, rather than tackling the very substantial decline and failure of their assets.

Instead of naming and shaming, or fining transgressors, the government and the sector need to agree a strategy to reverse the rot. Providers must admit that our homes need a fundamental upgrade and request external funding. Otherwise as liabilities crystallise, greater numbers of social landlords will be forced either into mergers or out of business.

ENGAGING WITH RESIDENTS

Any organisation providing services must work out what their customers want. While stock condition surveys are useful to objectively determine the overall condition of the housing (e.g. how long the roof will last, when the boiler needs servicing, etc) there is also the subjective test. This is like when a doctor orders a blood test, but also asks you how you feel. For years I insisted that every year we should visit every tenant in their home. The idea, at least originally, was to find out what residents had to say about their homes and neighbourhoods. We asked:

What do you like/dislike about your home?

Can you show me round and tell me about any features or problems you want me to know about?

What do you think of the local area?

Do you find it easy to get about within the home?

How is it in the block? Do you talk to your neighbours?

These open questions allowed the resident to bring their experience of their home to the attention of their housing officer, who tried to understand what specifically could be done to improve it, but also to observe if there was anything unacceptable about the home (like it not being safe, significantly overcrowded, or unpleasantly hot or cold). Critical observation skills were promoted instead of turning a blind eye. The idea was to combine resident feedback and staff insight with stock condition information, as we worked to renew and upgrade the stock over time. Alongside this, I spoke to thousands of tenants, held large meetings, visited residents at home, read their letters of complaint and organised improvement plans.

We discovered that there were just three things that all tenants wanted:

Get repairs that I ask for done quickly and to a high standard.

Listen carefully to what I need and resolve the problem.

Communicate with me.

PROBLEMS WITH DATA

The backlog of repairs and improvement problems is compounded by how little social landlords know and understand about the condition of each individual home. Today the regulator of social housing (RSH) requires this issue to be addressed:

Today, housing associations and local authority housing departments are hampered not just by insufficient resources but also by a lack of reliable data – on both the quantity and quality of their homes and on the needs and preferences of residents. Tenants suffer from confusion and delay in their interactions with their landlords because property data is inaccessible or incorrect. Housing associations’ ability to make rational long-term spending decisions or to evaluate strategic initiatives is limited by the age, quality and arrangement of their data. Additionally, both the regulator and housing ombudsman have acknowledged that the lack of reliable data undermines their ability to regulate effectively.

Much of our data has been piling up for decades, input by thousands of people, on many different platforms, including WhatsApp, texts, emails and paper, and does not begin to match modern requirements. We rely on spreadsheets, cardboard folders, email trails, and the memory of managers. When the government demands a list of homes over 18 metres, or a database of properties with damp and mould, housing associations send out a surveyor to measure buildings or scour their databases for mentions of mould. Several weeks later they have an approximate answer. This would be like Spotify having someone at the end of a telephone, putting a record on a turntable and playing it for you.

THE CURRENT INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY OFFER – PRODUCTS VERSUS PLATFORMS

During the interviews respondents indicated the key tasks associations should digitise are, assuming that technology could compatibly link each function: on and off boarding, rents, repairs, service charges, case management, asset management and complaints. Additionally, associations need trained staff available to deal with more complex issues.

To a greater or lesser extent, these key functions are embedded in the core housing management product. These systems include Aareon, Capita, Civica, MRI and NEC (Northgate), Salesforce and ServiceNow, supplemented by many add-on systems such as RentSense. It was hard to find anyone from a Housing Association who said that the core housing system (the underlying database) they were using was working well. No one I spoke to would recommend their product supplier. No one felt there was a great system out there if only they had the money, scale or time. There was a lot of disappointment. In response to this failure, many are now seeking help in the form of cloud-native SaaS platforms that provide an ecosystem, such as Microsoft Azure, Amazon AWS and Google Cloud. As a result, the huge internal support teams needed to keep core product systems working could be released for more productive work, as platform suppliers upgrade and maintain their systems remotely. In the last few years housing associations have introduced Azure or AWS as universal systems robustly designed for all industries, which update instantly, without additional charges. Users can customise and manipulate their own data, extract information from core systems, and make changes quickly in-house. Their reporting software is superior to that achieved by the old-fashioned legacy products which usually need connecting to performance management software and labour-intensive manual work to produce key performance information.

Today many associations combine both approaches, forced to retain the core legacy product but using the newer suppliers to draw out information. However, the platform vendors are marketing features which are being adopted, almost on an experimental basis; none have yet taken the needs of housing associations, especially smaller housing associations, and their tenants to heart, and sadly are yet another group who see social housing as a cash cow. Suppliers to the sector need to address the dissatisfaction which exists. Product suppliers must allow their housing association partners to access their own underlying databases. The platform suppliers must engage with the housing sector specifically and focus on solutions rather than features, and again allow associations access to, or to profit from, their own intellectual property.

Collaboration, Organisational Reform,

And interdependent working

Housing associations’ core purpose is to provide homes for people. A home is

not a property, but a place where people live when they arrive back from work or

society. It is where their family is based, and where they can relax and be themselves. Importantly housing associations do not deal with people or families in general, but with people in the context of their home. This is what makes us different from charities or social services. Our job is not to do anything for everybody, but simply to provide homes and the services associated with homes such as investment, repairs and communal cleaning.

In addition, the concept of home does something more for people than provide

a safe haven. It affects our sense of self. By adopting a higher “lettable standard” we

challenge stigmatisation, and our customers experience greater satisfaction with

their quality of life. An aspirational home is not a “roof over our heads” - it confirms

our social and personal worth, it aids self-esteem and the respect of friends, family

and community.

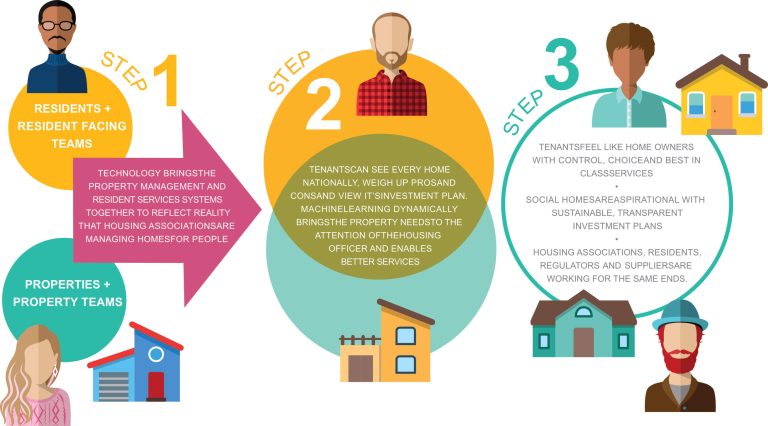

Today’s housing associations routinely divide management of the home from the

management of tenancies. An institutional segregation between the system,

processes and staff teams that focus on people versus the systems, processes and

staff teams that focus on buildings, undermines this fundamental view of a home. We have created two separate departments and two siloed system applications,

between which information cannot be shared.

Today, housing associations and local authority housing departments are hampered not just by insufficient resources but also by a lack of reliable data – on both the quantity and quality of their homes and on the needs and preferences of residents. Tenants suffer from confusion and delay in their interactions with their landlords because property data is inaccessible or incorrect. Housing associations’ ability to make rational long-term spending decisions or to evaluate strategic initiatives is limited by the age, quality and arrangement of their data. Additionally, both the regulator and housing ombudsman have acknowledged that the lack of reliable data undermines their ability to regulate effectively.

The two-silo approach appears logical. On one hand we have the residents, and the resident-facing teams, who operate the Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system, dealing with complaints and requests, the day-to-day and urgent repairs demand. Then on the other hand, we have the properties, plus property teams who focus on making sure the homes are in acceptable condition, and whose main reference point is the asset management database. The surveyors concern themselves with the objectively determined property need and manage resources carefully over multi-year programmes. The two staff teams work on different time frames (immediate vs 30-year programmes), with different IT systems, funding streams, stakeholders, contractual terms, pressures and cultures. This fissure

between tenant and property is disastrous and explains why housing associations fail.

This needs to change. We need an interdependent approach. Asset management and planned repairs (the needs of the home) must relate to and influence responsive repairs (and things that tenants desire). Associations which think and act in an internally collaborative manner could change the culture which would lead to a different relationship with technology. Collaborative approaches between teams would reinforce and strengthen the residents’ experience of home. Ideally, the whole sector would work together to achieve this so that no tenant, region or community is left behind. With a new vision and culture housing associations could finally get the technology they need to make a real difference.

Working With Residents to

Set New Specifications

Currently, the sector struggles with resident consultation, involvement, empowerment, scrutiny and general interaction. It also feels like a battle to meet what the regulator requires. There is a plethora of theories, models, and even technologies to do the job. The reality is, most of this causes confusion, resentment and time-wasting on both sides. Residents are inevitably most concerned about their own homes. Yet there are many times when tenant “representatives” are criticised for using resident meetings to bring up their own issues and complaints. However, if the starting point is changed to a dynamic person-plus-property understanding of what “home” means, the tension is dispelled. The landlord’s priority is to understand how the resident experiences their home and to work relentlessly to put this right.

A power-sharing outlook means putting the tenant in charge of their home and neighbourhood. This will come if associations can genuinely begin to overcome the property vs tenancy divide. In this way, residents will provide the necessary requirements, which will influence how we specify the technology we need. Today’s priority is to work with residents and building experts, to clearly establish the physical needs of the home. Each home requires a plan to upgrade it to modern standards over a realistic period influenced by resident preferences, choices and requirements. A new aspirational “homeowner” standard, negotiated with tenants, housing officers and maintenance staff, needs to be realistic in terms of time and cost, but we can no longer accept deteriorating homes which become a liability. The underlying asset management system would optimally plan investment in the stock to quickly produce the best outcomes. Crucially, it would link specific programmes like building safety, sustainability and cyclical programmes so that all investment in a property works together to enhance the home and the tenant experience. Such a strategic asset investment programme also delivers full transparency.

New information technology solutions are required to ensure that asset management data dynamically informs the day-to-day repairs and property related complaints raised by tenants. Intelligent automation brings the property needs to the attention of the housing officer in real time. Complaints and requests from residents can finally be seen and understood in context, making sure that decisions are no longer random, but are based on reliable data. Working like this, using big data to surface systemic issues behind resident complaints, would instantly rationalise spending, allow predictive modelling and boost satisfaction.

INTERDEPENDENCY BETWEEN HOUSING ASSOCIATIONS

All this work would be exponentially more fruitful if the sector worked together.

Tackling the backlog of repairs, finding ways to listen more effectively to residents,

upgrading and simplifying technology, deciding on key performance indicators that really matter, reinvigorating tired environments and communities – however, all of these challenges take time and energy to bring about. Imagine how much better this would be if Associations could collaborate, sharing the learning and moving forward with joint initiatives. With support from other stakeholders, the sector should consider regional or specialist collaboration circles to address

the key functional challenges which exist today.

SETTING THE STANDARD: A COMMON PLATFORM FOR SOCIAL HOUSING

Back in 2017, challenged by government concerns that technology was not being deployed sufficiently in the public sector, the RSH produced Regulator of Social Housing: Innovation Plan. It considered how the sector might innovate and use the huge potential of technology, mentioning “Uber and Airbnb” to emphasise the disruptive potential of technology to completely transform established industries.

Uber and Airbnb are digital business models, classic two-way (sometimes called a multi-sided) platforms – a technology platform that allows two distinct but interdependent groups of people to interact smoothly and independently. In essence the platform connects buyers and sellers, so both can benefit. It disrupts as it eliminates the middleman (plus the associated costs and bureaucracy) and empowers both buyers and sellers. These platforms directly connect people who need things, with people who can supply them. Airbnb, for example connects travellers with hosts. Airbnb provides the technological infrastructure, such as a mobile app, allowing hosts and tourists to connect easily, and it takes a cut on each transaction. The app includes features for booking a room, facilities, payments and rating the quality of accommodation.

Housing association services are more complicated than getting a taxi or finding a room in Amsterdam. Residents are not ‘customers’ in the true sense. The needs associations aspire to meet are complex and social, rather than consumer wants. Mainly because three key elements are at play – residents (people), homes (property) and community (place) – there is a different level of complexity. The housing association is central because it owns the homes – giving it a responsibility for the property and an obligation to the people who rent them, and to the place – the local community, location and environment where the housing is situated. The have to take community needs and local and national political priorities into account.

If a housing associations were viewed in a similar way to Airbnb etc, they would need a multi-sided platform that includes residents who use the platform to get their needs met, and a group of customer-facing staff (or bots) who sit on the other side, fulfilling tenant demands. Behind the customer facing staff (or bots) are a range of suppliers, able to access available jobs like ‘exterminate mice’, ‘fix immersion heater’, ‘do gas safety check’. An example of this is Plentific. The model that Plentific has developed is a good example of a platform linking landlords with companies who bid to do specific repairs and improvement work.

The advantage of this concept is that it is built from the outside in, giving the resident the kind of experience they receive from the best digital vendors such as Amazon.

However great technology is not everything. Social housing will always need a human face, and an attitude of understanding and empathy. Not everyone can self-serve, and a proportion of issues and needs are complex and cannot be dealt with by technology. This “additional” service is crucial in social organisations. While the majority are not “vulnerable” and prefer a quick, reliable service, there are people living in social housing who have greater needs for support and help. They want relationships with us, not just transactions. Also, these relationships are not linear, they can be costly, and associations may need to recruit help from other services such as health and local government. Often housing associations are part of a wider eco-system rather than the sole provider and many of the issues faced do not have a simple, one-step solution. Our desire to help our residents beyond their immediate housing needs and to improve things for communities means that on some occasions the focus on homes and services must be holistic rather than transactional.

NATIONAL SOCIAL HOUSING PROPERTY DATABASE

Consequently UX (user experience) is much more complicated than designing something simple, instinctive and elegant. It needs to be accessible to residents, safe and secure, based on a concept of equality and empowerment, rooted in a notion of aspiration and mobility rather than dependency. This is where sophisticated design is important, led by customers who will use it. As this is not a matter of exchanging money for goods and services, restrictions on what is provided will be necessary. These restrictions need to be thought through with the difficult question of “discretion” carefully considered. For example, vulnerable, disabled residents, or families with young children, may be given more services than people without these additional needs, but adjudicating these issues is challenging. It is probably best to see these issues as “the exceptions” that must be dealt with through a personal (human) interaction, leaving the platform to deal with the 80% of routine transactions. We should plan for the rule not the exception and make a clear distinction between “transactions” (which are ripe for digital delivery) and “interactions” which are longer-term, and relationship based, demanding human empathy and insight.

A common platform for social housing could start in a fairly simple way with new features being designed and introduced by collaboration circles within the sector, as it gradually takes on more and more labour intensive, routine work from staff.

Data is both the greatest problem currently facing Housing Associations but also the greatest opportunity that could be the “game changer” if we get it right. To illustrate this, people said, “We are not even sure how many homes we have!”. We have tons of data but it is not currently reliable, clean or useable. Yet data is the key to making operations a huge success.

As housing associations have been instructed to upgrade their asset data, to respond to regulator demands and to increase customer satisfaction, there is an opportunity to collaborate on how it is done.

The Finance Reporting Council sets UK accounting standards. The housing statement of recommended practice, with proper consultation and input from sector experts, periodically updates the standards used by Housing Associations. This means that all accounts produced by Housing Associations are on the same basis allowing detailed comparison. In fact, the Regulator of Social Housing (RSH) routinely carries this out through its annual global accounts analysis, effectively combining the accounts of all housing associations to reveal trends. Many housing associations and vendors to the sector also make use of this data for their own purposes.

Housing associations have so much valuable data that is never leveraged, just stored. Yet we are only a few steps away from using our data every day to solve immediate problems and make sensible plans for the future. A sector-wide, and government-led national social housing property database would be a relatively inexpensive and rapid way to drive improvement in social housing, transforming the customer experience while reducing costs. It would help housing organisations manage their property data to improve the standard of housing; address safety concerns more rapidly and possibly with shared, area-based solutions; and increase accountability and good governance.

A single, simple, limited-in-scope database needs a universal data structure, common formats and connectivity standard which makes it much easier to share data between platforms, or between organisations. The specification of the technology should be carried out with the regulator and government (enlisting the experience and expertise in the Office of National Statistics and the government digital service). This one standard must become obligatory for all. Private sector companies could compete to develop and provide the technology, informed by housing data standards work carried out by Housing Associations’ Charitable Trust (HACT), having absolute clarity about what is required and a guaranteed marketplace. Despite its obvious cultural differences, the financial sector has harnessed the power of data analytics and automation to improve decision-making and customer experiences through open banking. Customers use mobile applications to pay bills, monitor balances, and compare products. Banks leverage customer data to provide customised recommendations. Also, modern banks – like Monzo, Revolut, and Starling have disrupted or partnered with established financial institutions and technology firms to overcome the limitations of legacy systems.

Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and data-sharing frameworks

The advent of open banking, benefitting from open data models, has driven more significant change – innovation, greater transparency, and superior decision-making. As a result, the financial regulator can demand access to certain data sets. Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and data-sharing frameworks have been instrumental in the protection and efficient dissemination of financial data. Most importantly data standardisation has enabled the establishment of uniform data models and formats for effective sharing and application.

A database, by definition, is a structured collection of data that is organised in a way that enables efficient access, management, and updating. Modern principles would require it to be near real-time, cloud-based and updated through APIs, federation, automatic file ingestion. The high-level results would be published though a website and the internal stakeholders could subscribe to more detailed insights through an easy-to-use online business intelligence application.

Modern principles would require it to be near real-time

Provider

Ownership, Manager , Parent, Tenure type, Local authority

Property

Uprn, Postcode, Address, Town, Construction, Type, Year, Constructed, Bedrooms, Homes in block

Condition

Decent home, Kitchen date, Bathroom date, Out of Management, Disrepair, Hhsrs (housing health and safety rating system)

Energy

Heating source, Epc, Epc band

Provider

Gas, Electrical, Asbestos, Fire, Lift, Damp and mould

Ownership is important in terms of design and delivery, but the Government must decide this is the right thing to do, as it has in relation to financial and accountancy standards inside and beyond the sector. It must mandate social housing providers to work together to agree adequate data standards and to procure technology to deliver hyper-transparent data which can be compared, interrogated, evidenced, and shared with ease to improve outcomes for social tenants.

The necessary technology has a proven track record, and datasets are emergent based on the specific solution. The financial sector and government (DVLA, DWP, Passport Office, GDS, Covid-19) have paved the way for successful open data initiatives. Housing associations maybe reluctant to collaborate, but it is in their own interests, and that of their residents, to do so.

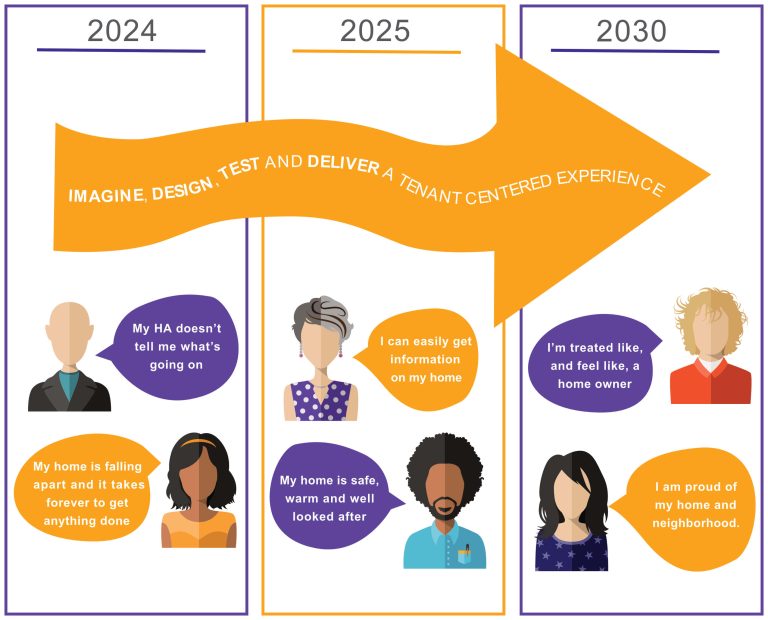

The Future

This necessitates better organisational arrangements within housing associations, coalescing around the need for the organisation-as-a-whole to focus on tenants’ homes. The threats we face demand that we work with residents; replace property vs people silos with interdependent teams; and establish new ways to collaborate across associations.

While we let sub-standard homes we jeopardise the health, safety and well-being of our tenants. We must set a new, enhanced “lettable standard” on par with our new build specification, and draw up plans to improve every failing home.

The existing stock is failing because it has been underinvested in for decades. The value and utility of our homes will drop if the backlog of repairs and improvements is not addressed. We owe it to our residents and society to create a medium-term investment plan for every home we own.

Better technology would support associations to meet new expectations and standards. Working collaboratively the sector could specify or adopt new, simplified information technology to support its key tasks. A common platform for social housing (2.4, above) seems to be a promising project that housing associations could collaborate on, with the objective of “disrupting” themselves in a controlled manner. Self-service would liberate the majority of residents.

For too long we have pushed active tenants into participating in our governance structures, missing the first step in building trust and support. Residents often become active because they want their home fixed. Once they are confident that they are being heard, they will offer relevant and helpful feedback to improve the service for everyone.

For the sector as a whole a national, social housing property database is a start (see 2.5, above). Adopting the principles of open data would enable residents to access information about their home. Landlords would know much more about their homes and could use reliable, real-time data to support decision making about day-to- ay repairs and other tenant requests. The sector and the regulator would be able to correlate global data to support strategic planning and development.

Timetable And Building Momentum For Change

Housing associations have many advantages – a huge number of homes, largely paid for, available at low rents; committed staff and board members; and a marvellous mission – to fight homelessness and provide homes and communities for residents. Sadly, we are struggling today – not just to provide more new homes for one million or more families and individuals who need them. We are also struggling to provide the quality of homes and services that our four million families and individual residents deserve. In the digital age, technology provides enormous and unprecedented possibilities for sharing, collaboration and innovation. This paper encourages the government, its regulators, the sector and its residents to imagine a different future. What is to be done?

The sector is not short of good analysis, ideas, or proposals. We have intellect, passion and a voice. Only a year ago the NHF/CIH published the Better Social Housing Review, and many of the ideas discussed there also appear here.

Today the sector faces some very real threats. Money that was once allocated to associations has been redirected to private bodies and local authorities. The self-replicating financial model for building thousands of new affordable homes is broken. Shelter has shown we sell or demolish more social homes than we build each year. The stock is in poor condition – worse than we have admitted - and it is rare to hear residents praising their landlords. The relentless reputational damage has hurt not because it is unfair, but because it is true.

There is a simple choice. We can ask the government to engage with us so we can revisit the basics and have a fresh start. This is certainly a possibility with a new government expected shortly. Or we can act together to seize the moment that is upon us.

This White Paper exists because I believe these suggestions are practical, affordable and achievable. Many people are afraid of big ideas or tackling the most difficult problems, but computers and the internet have completely changed the context. The proposals focus on embracing technology, but technology in the context of reframing what we are about. Our operating model is as old as some of our properties and was designed to all intents and purposes by Octavia Hill over hundred years ago.

As Nelson Mandela said, “It always seems impossible until it is done”.

INDICATIVE TIMETABLE AND PROPOSALS

Date

Ideas

Collaborations

Actions

YEAR 1

Building momentum For change (associations, Residents, Politicians)

Associations Decide On How To Collaborate And Set Up Collaboration Circles

Design An Open Data Social Housing Property Data Base

YEAR 2-3

Establishing What Cultural And Technological Changes Could Catalyse The Changes We Want

Regional And Sectional Housing Groups Have Common Action Plans

Design A Common Platform (Replacing Crms) For The Social Housing Sector

YEAR 4

A Clear Vision Emerges On What The New Housing Association Sector Stands For

The sector works with the government to review how positive change can be accelerated

Clear Standards For Data Collection And The Specification Of Technology Are Adopted

YEAR 5

National Dialogue With Residents On Progress To Date, Feedback And Proposals

Customer Facing Association And Property Staff Work

Together As Standard

All Associations Have A Costed Improvement

Programme For Their Stock, With Transparency At Home Level

YEAR 6

The media and other critical voices notice that things are getting much better

Platform suppliers have listened carefully to the

sector and have designed new products with and for them.

All associations routinely use reliable real time data to make decisions and to defend their strategies

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following people who helped me with this work. My Buena associate Dr Nick Johnson conducted the literature review and provided a supportive intellectual challenge, EK Daley of 4ED carried out the initial edit, and Gus Kanda of Kanda People the final edit. Kate Doodson of Cosmic introduced me to the work of Dr Gavin Beckett on local government as Platform Organisations. Steve Dungworth of Golden Marzipan created the proposal for the Social Housing Database. Matt Ballantine challenged the siloisation of associations. Paul Taylor put me in touch with Professor Mark Thompson who provided lots of ideas on open standards in the public sector.

Colin Sales and Julia Mixter provided great insights and encouragement. Kate Still is a huge advocate for major change, and her writing and conversation strengthened my conviction. Michael Wallis of Corkewallis and Matthew Curtis of Curtis & Co helped me think about the future of social housing, providing the main diagram. My daughter Charlotte Johnson provided the pamphlet design and Mike Lewis proof-read the document.

In addition, I conducted 45-minute interviews with the following people about their experiences, and I am particularly grateful to them.

Steve Aleppo, ed finance and governance, Eastlight Community Homes

Matt Ballentine, Digital Transformation specialist, equal experts

Jacqui Bateson, MD, hack housing

Tim Cowland, digital transformation lead, Red Kite Community Housing

Stewart Davison, MD, Elehan consultants

Kate Doodson, joint CEO and digital transformation consultant, Cosmic UK

Amina Graham, ed people and systems, housing 21

Jayne Hilditch, freelance finance director

Anita Khan, CEO of Tower Hamlets Community Housing

Claire Lea, senior consultant, Socitm advisory

Mike Lewis, commercial director, Equantiis

Peter Lunio, director of Golden Marzipan

Julia Mixter, director of transformation, Raven Housing Trust

David Morgan, executive managing director, wates property services

Ninesh Muthiah, founder and CEO, of Home Connections

Yogeta Partridge, MD, Rydeo consultants

Clare Paterson, data protection expert

Rajiv Peter, CIO, Notting Hill Genesis

Colin Sales, CEO, 3c Consulting

Phil Shelton, Connecting Tech

Kate Still, CEO of recensere associates

Paul Taylor, innovation coach, Bromford Group

Neil Topping, Data Futurists and Paradpo

Mark washer, ce, sovereign network group

Ian Wright, founder and CEO, of Disruptive Innovators Network

SOURCES

Ambrosi, “Neighborhood emphasis for the sector ‘rebranding’”, inside the housing, 18 August 2002

Gavin Beckett, how could UK local government become a platform organisation? Perform green, (first posted on 1 February 2018)

CIH and NHF, better social housing review, December 2022

Stephen Delahunty, “Two-thirds of senior council housing staff not qualified enough To meet the new requirements”, inside housing, 8 August 2023

Dluch, English housing survey 2021 to 2022, 15 December 2022

Dluch, global accounts of private registered providers, 10 January 2022

Dluch, consumer standards consultation, 16 august 2023

Steve Dung Worth, the case for a national database of social housing property, 27 November 2023

HACT, UK housing data standards, 2018 and updated

NHF, accounting and the housing sorp

NHF, better together, 2023-2026, 26 July 2023

Plentific platform for contractors, https://www.plentific.com/contractor/

RSH and HCA, a regulator of social housing: innovation plan, 27 March 2017

Shelter, net loss of social housing, January 2023

Kate still, “We need to talk about co-regulation”, LinkedIn, 9 August 2023.

Professor Mark Thompson, digital strategy, and Leadership, 2021

Robert b. Tucker, “How does Amazon do it?”, Forbes, 1 November 2018

UK parliament, social rented housing (England): past trends and prospects, 13 August 2022

UK parliament, housing in England: issues, statistics, and commentary, 10 November 2022